Acogedora, relajante confortable.™

Acogedora para jugar o descansar, Mira está diseñada para calmar y reconfortar al bebé, y permite su transporte para tenerlo siempre cerca. La mecedora y asiento 2 en 1 mece suavemente al bebé siguiendo su movimiento natural, desde recién nacido hasta sus primeros años.

Un lugar seguro para el bebé

Un espacio seguro y sostenible para que el bebé juegue o descanse cómodamente. Cuenta con las certificaciones GREENGuard® Gold, JPMA y FSC™, lo que significa que la mecedora Mira se sometió a rigurosas pruebas para garantizar un mayor nivel de seguridad del producto.

Diseño que se adapta a los padres

Ajuste de reclinación orientado hacia los padres y de fácil acceso, con tres niveles diferentes para elegir a medida que el bebé crece. No será necesario buscar detrás de la mecedora mecanismos difíciles de usar, Mira ofrece facilidad a los padres y comodidad al bebé.

Fácilmente transportable

Diseño portátil que se pliega para guardar, con un asa de transporte integrada en modo plegado para facilitar el traslado. Además, incluye una bolsa de almacenamiento, con múltiples asas que ofrecen mayor comodidad al viajar y permiten un guardado seguro.

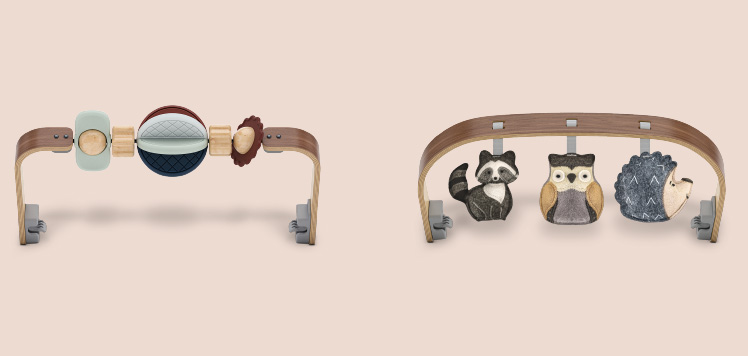

Toy Bar Accessories

Diseñado para inspirar a los niños a ejercitar el desarrollo de la motricidad fina y la coordinación óculo-motora, nuestros dos modelos de accesorios para la barra de juguetes presentan texturas divertidas y atractivas que seguro cautivarán al bebé.

Los accesorios se venden por separado.

Incluye un protector del asiento.

Incluye un protector del asiento que otorga una capa adicional de comodidad, calidez y suavidad para el recién nacido.

Asiento de doble confort con malla transpirable

Tejidos cómodos, transpirables y reversibles que garantizan un uso prolongado y se adaptan a todas las estaciones.

Diseño 2 en 1 para acompañar el crecimiento del bebé hasta la primera infancia

Permite un uso prolongado desde el nacimiento hasta los primeros años. Simplemente se debe retirar y voltear la tela al volverla a colocar sobre la estructura.

Telas extraíbles y lavables

Desabroche la tela y colóquela en la lavadora para un fácil y rápido lavado.

Specifications

- Asiento de doble confort con malla transpirable

- Incluye un protector del asiento

- Easy Parent-Facing Recline Adjustment

- Diseño 2 en 1 para acompañar el crecimiento del bebé hasta la primera infancia

- Certificados GREENGUARD® Gold, JPMA y FSC™

- Asa de transporte integrada en modo plegado

- Arnés acolchado ajustable

- Telas aptas para lavar a máquina

- Incluye bolso de almacenamiento con múltiples asas de transporte

- Accesorios para la barra de juguetes diseñados con el fin de que los bebés ejerciten la motricidad fina y la coordinación óculo-motora